Article

Physicians share surgical pearls for successful trabeculectomy

Author(s):

Several techniques can result in better surgical outcomes for patients

Glaucoma surgeons highlight elements of their personal trabeculectomy technique, which can optimize long-term IOP control and minimize the risk of early and late complications.

Reviewed by Paul Palmberg, MD, PhD, and Henry D. Jampel, MD, MHS

Variations in trabeculectomy technique aim to optimize long-term IOP control and minimize the risk of early and late complications. Paul Palmberg, MD, PhD, and Henry D. Jampel, MD, MHS, shared elements they have incorporated in their surgical approach that contribute to successful trabeculectomy.

Dr. Palmberg said that his current technique has been developed during a career of more than 40 years.

“In a large group of patients, it has achieved long-lasting IOP control in the low-normal range with no net visual field progression over a decade of follow-up, and it has been associated with a low rate of hypotony,” said Dr. Palmberg, professor of ophthalmology, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL.

The first consideration is how to avoid bleeding and the need for excessive cautery, both of which promote scarring, he reported.

Avoiding bleeding

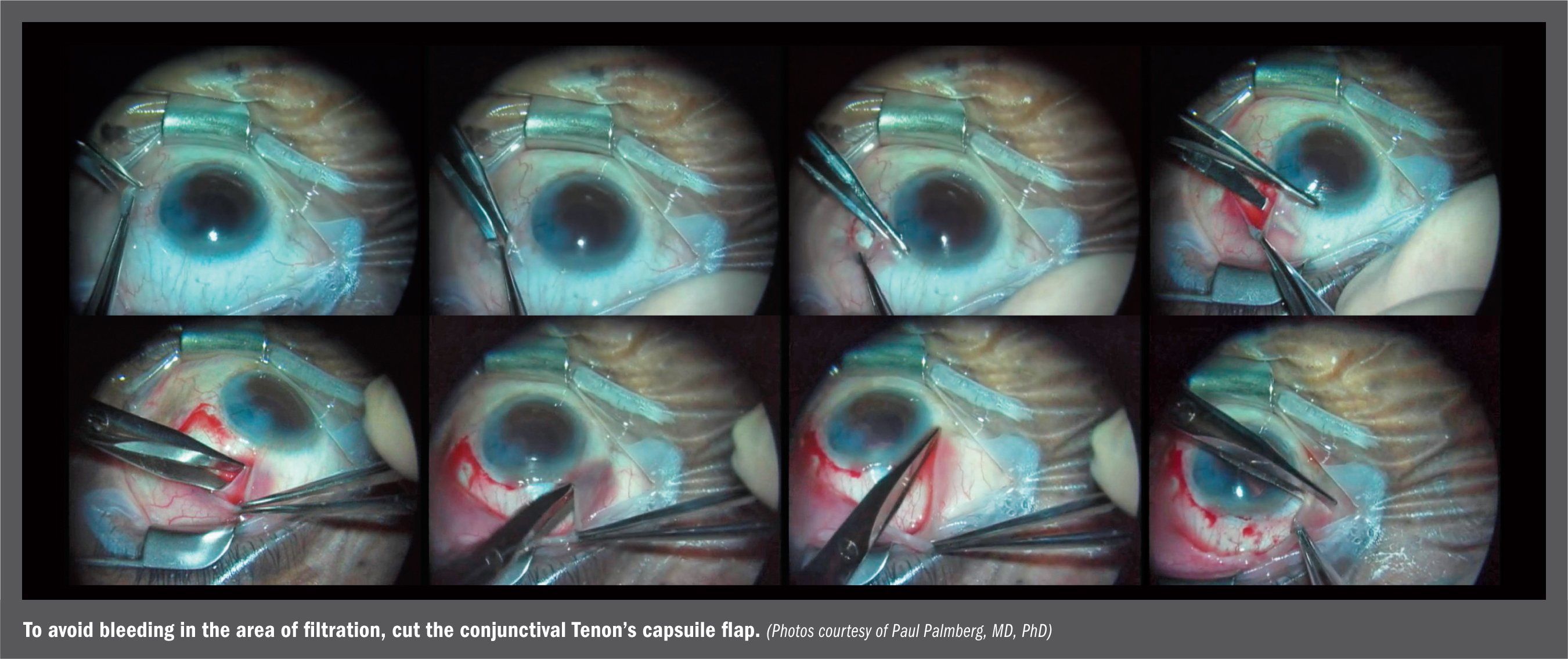

To avoid bleeding in the area of filtration, he cuts the conjunctival-Tenon’s capsule flap only far away from the filtering site, beginning with a lateral relaxing incision down to sclera, demonstrated in the photo above.

Dr. Palmberg said he then everts the conjunctiva and passes the Westkott scissors behind the insertion of Tenon’s capsule, which is 1-2 mm behind the insertion of the conjunctiva, in order to enter the potential space under Tenon’s.

The scissors are then advanced under Tenon’s, lifting it above the scleral surface vessels, pulled down toward the limbus, and then one blade is inserted and the conjunctiva and Tenon’s capsule are cut together at their insertions.

“The only bleeding is at the insertions, where spot cautery can be applied,” Dr. Palmberg said. “This avoids the problem that I see with smaller conjunctival flaps, in which the scissors pass blindly under the flap and cut into the vessels in Tenon’s, and mitomycin-C (MMC) sponges come out soaked in blood.”

He then uses the scissors to penetrate through the intermuscular septum to each side of the superior rectus. MMC 0.4 mg/ml is then applied using large (4 x 4 mm) thin pieces of cellulose sponge cut from a spear sponge.

The sponges are placed through the opening in the intramuscular septum to each side and along the limbus. The sponges are removed after 3 to 5 minutes and inspected to see that they are intact.

Then, the eye is rinsed with 5-10 ml of saline.

“I have found that the wide application of MMC, introduced by Sir Peng Khaw, greatly reduced bleb problems by producing more diffuse blebs,” he said.

Dr. Palmberg added that prior to MMC application, he creates a “safetyvalve” tunneled trabeculectomy. In this technique, a 3-mm groove is made at two-thirds depth in the 12’ o’clock position, 1 mm behind clear cornea. Then a crescent knife is used to tunnel 2 mm forward, 1 mm into clear cornea.

A bent paracentesis blade is then used to enter the anterior chamber, and a 0.75 mm Kelly Decemet’s punch is used to punch out two side-by-side pieces of the posterior lip of the internal ostium. Balanced salt solution is then injected into the anterior chamber to inflate it and to initiate aqueous flow.

The flow is observed to equilibrium, using a cellulose spear sponge to gently touch the groove to absorb fluid, and then the points of light in the groove are watched as they disappear as fluid fills the groove. The IOP at equilibrium flow is estimated by pushing on the cornea with a 30-gauge cannula, with a goal of having this wound set an IOP of about 4-6 mm Hg, Dr. Palmberg said.

Additional punches

Additional punches or cutting down on the sides of the tunnel are then performed until that goal is reached. Two 10-0 nylon sutures are then placed, and their tension adjusted to yield an equilibrium IOP estimated at 8-12 mm Hg. “That this is an effective means of adjusting the scleral resistance is confirmed by the observed mean IOP of 10 mm Hg on day 1 postop,”

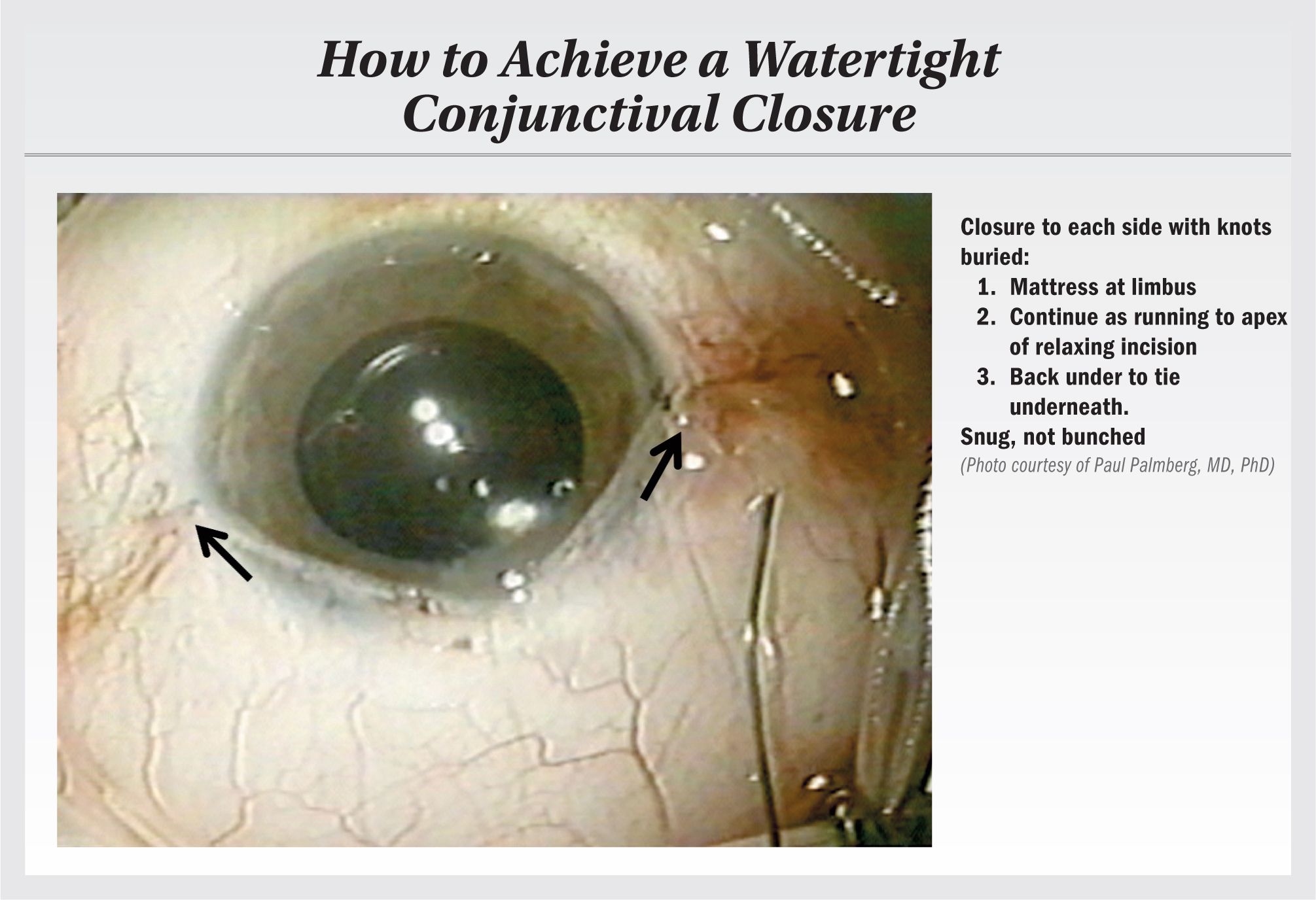

Dr. Palmberg said. The conjunctival flap is then closed with a buried 10-0 nylon mattress suture at 12 o’clock.Buried mattress sutures of 8-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) are placed at 3 and 9 o’clock, with the conjunctiva-Tenon’s capsule pulled tight along the limbus to be impaled upon the emerging needle. The suture is then continued as a running suture to the end, and an apical bite is passed back under the flap on each side to be tied underneath the flap, so that the single knot to each side is buried, with a snug and water-tight closure, without bunching the tissue.

Scleral bites

Dr. Palmberg emphasized that the scleral bites of the closure need to pass vertically into the tissue, then pass along in sclera, and also exit as vertically as possible, producing “square wave bites,” rather than skimming bites, in order for the fragile conjunctiva to be supported and not torn.

Considering fashion stitches, Dr. Palmberg said he wondered how seamstresses could sew a fragile material like silk without having the thread claw holes.

“Looking at the inside of a seam in my wife’s silk dress I saw seam binding tape and noted that the seamstress aligns passes through the tape with passes through the silk on each side so that the closure compresses, but does not tear the material,” he explained.

“If you do not similarly support the conjunctiva with matched scleral bites, your sutures will gradually claw through the scleral bite at the skimming entry and exit and loosen the conjunctival closure, typically leading to a limbal leak at about three days.”

Dr. Palmberg said that his technique is fairly efficient, involves no device cost, and obviates the need for an iridectomy because there is no flow until the anterior chamber is formed. In addition, the technique also is associated with less induced astigmatism because the flap sutures do not need to be very tight.

“But most important are the outcomes showing it has achieved an average IOP of 11 mm Hg over a decade of follow-up with no net field loss in the group, and a success rate, defined by an IOP < 15 mm Hg, of 90% at two years, 73% at five years, and 60% at 10 years,” he said.More pearls

Highlighting a few steps in his trabeculectomy technique, Dr. Jampel, Odds Fellows professor of Ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said he initiates the conjunctival peritomy 1.5 to 2 mm posterior to the limbus, a technique he learned from Eugenio Maul Jr., MD, and places a 50/50 mixture of lidocaine and bupivicaine through the snip incision for local subconjunctival anesthesia.

When applying MMC, Dr. Jampel uses an 0.2 mg/mL concentration and places it through the snip incision. He opens up the incision so that it is parallel to and about 2 mm posterior to the limbus. Dr. Jampel then performs the conjunctival dissection posteriorly and to the sides. After the trabeculectomy flap has been made, Dr. Jampel preplaces two releasable sutures of 10-0 nylon using a technique shown to him by Jayant Iyer, MD, a fellow who came from Singapore.

Singapore sling

“I have named this technique the Singapore sling releasable suture. It is made by placing a backhanded suture that starts in the sclera, comes out through the cornea, and then goes back in through the flap,” explained Dr. Jampel.

After completing the scleral flap dissection, creating a sclerotomy with a Kelly Descemet’s punch, and iridectomy, he then sutures the flap with the releasable sutures and places a third releasable suture anchored in the cornea. He said he then closes the conjunctiva with two 10-0 nylon wing sutures whose knots are buried.

“I feel that by pulling the posterior lip up against a residual ‘bolster’ of conjunctiva at the limbus, I can achieve a watertight closure without the need for a central suture,” Dr. Jampel concluded.

Disclosures:

Henry D. Jampel, MD, MHS

E: hjampel@jhmi.edu

This article was adapted from Dr. Jampel’s presentation at the 2019 American Glaucoma Society annual meeting. Dr. Jampel has no relevant financial interests to disclose.

Paul Palmberg, MD, PhD

E: mitodoc@aol.com

This article was adapted from Dr. Palmberg’s presentation at the 2019 American Glaucoma Society annual meeting. Dr. Palmberg has no relevant financial interests to disclose.

Newsletter

Don’t miss out—get Ophthalmology Times updates on the latest clinical advancements and expert interviews, straight to your inbox.

259 Prospect Plains Rd, Bldg H,

Monroe, NJ 08831

All rights reserved.