‘The right thing to do’

On the rippling effects of alleviating suffering for free

By Peter J. McDonnell, MD

What kind of idiot runs a company that makes something and gives it away free to 200 million poor people every year?

As a lad, I loved to read the magazine National Geographic. The eagerness with which I anticipated its arrival in the mail is rivaled today only by the thrill experienced by ophthalmologists as they rip the plastic wrap off their latest copy of Ophthalmology Times.

For a kid from a small town of 5,000 on the Jersey shore, National Geographic was a window to an amazing and strange world. In the photos, people dressed differently, acted differently, ate unusual foods, and engaged in remarkable activities. Padaung women added rings successively to their necks, stretching out their cervical spines. (I remember the magazine included an x-ray of the neck of one woman showing the displaced vertebrae.)

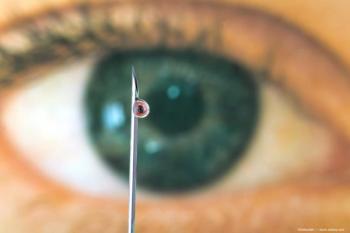

Particularly fascinating were the amazing diseases. People went blind from strange infections like onchocerciasis, came down with liver diseases from disgusting little liver flukes, and suffered disfiguring lesions from leprosy. To this day, I recall the morbid fascination with which I stared at the truly incredible effects of “elephantiasis,” in which poor people would develop grossly thickened extremities, especially the legs and male genitals. There was no treatment for the sufferers, and I wondered how they were able to endure.

“I hope this never happens to me,” I recall saying to myself.

Smart move or ‘dumb’ move?

In subsequent years, Roy Vagelos came into the picture. Roy, a physician and biochemist, had developed a scientific approach to identifying possible new drugs based upon targeting specific enzymes, and he rose quickly to become the chief executive officer (CEO) of the pharmaceutical company, Merck.

Merck had a drug, ivermectin, which had been developed for other purposes. Merck tested it in Africans going blind from onchocerciasis and being disfigured by elephantiasis (both due to microfilaria). And it worked. Amazingly well.

But from a business perspective, this was a “dumb” move. The many people with diseases like onchocerciasis and elephantiasis could never afford to pay for drugs, and their governments either could not or would not. And if these millions of people did take the drug and experienced some type of unanticipated side effect, the current sales of ivermectin would be jeopardized in the developed world, leaving Merck to take a big hit financially.

But Vagelos decided that Merck would provide the drug free to poor people who needed it, saying it was “the right thing to do.” Merck’s employees, according to the CEO, were developing new therapies to alleviate suffering, not to maximize profit. Today, an incredible 200 million people on our planet, about 3% of the world’s population, take ivermectin for free every year.

Onchocerciasis is now largely under control in Africa and the Amazon River basin of South America, and certain countries where the disease was once endemic have been certified to be totally free of onchocerciasis. A similar dramatic impact has occurred with lymphatic filariasis, the disgusting elephantiasis affliction that so impressed me when I was a boy.

Good PR

I told my non-medical student daughter about Vagelos one day. I said it must be wonderful to have helped so many people in the world, but that what he did could be looked upon as a bad business decision.

“But all the good PR for his company is probably worth a lot,” she replied.

But very few people, it seems to me, are aware of what Vagelos and his company have done. Similarly, I think most of the public in my country and around the world do not know that many millions of doses of azithromycin are provided free by the manufacturer to poor Africans afflicted with or at risk for trachoma.

Newsletter

Don’t miss out—get Ophthalmology Times updates on the latest clinical advancements and expert interviews, straight to your inbox.